For my first post, I want to write about something that has become near and dear to my heart. It’s philosophy, but I promise I have done my best to make it palatable.

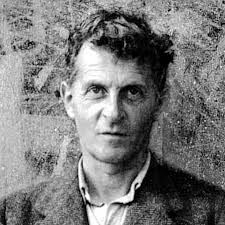

My chief philosophical interest this year has undoubtedly been the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. I ignored him for so long– mostly out of fear, but partly out of allegiance to one of my philosophical saints, Bertrand Russell, with whom he had vigorous disagreements. This was a great mistake. While challenging, Wittgenstein’s works are incredibly rewarding. Today I want to share just a humble slice of one of his many great ideas.

Without going very deep into Wittgenstein’s history, I’ll say that he rose to prominence in the early 20th century during the birth of what would later be called Analytic Philosophy, and he got his start under the tutelage of the reigning king of analytic philosophy, Bertrand Russell. Wittgenstein was deeply saturated in the mathematical philosophy of the day, and he was obsessed with finding the solutions that the analytics all sought, which was nothing less than to understand and justify the foundations of mathematics and logic itself. Russell viewed Wittgenstein as something of a chosen one — the one to lead the next generation of philosophy in the quest for which Russell was getting too old. But Wittgenstein went to war, and, according to Russell, the war changed him.

Wittgenstein wrote his small but great work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, while a soldier in World War I, and sent it to Russell for publishing in 1921. The book is a truly magisterial blend of mysticism, logic, and language, and it’s as difficult to understand as it is humbling to behold. Wittgenstein even claimed Russell never understood it. To do any sort of justice to the ideas in the Tractatus, I would need to take much more time than I am willing to spend here (and probably even then I would do it no justice), so I will just be writing about one very important idea.

In the TLP, Wittgenstein famously presents what has become known as the show/say distinction.

4.1212. What can be shown, cannot be said.

This distinction, Wittgenstein believed, was the key to healing our philosophical ailments. How? To get a better grasp of this distinction, we will briefly need to look into some of Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language.

In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein develops three categories that sentences may fall under. These are sense, senselessness, and nonsense. These categories connect, in varying degrees, to what some view as the crucial doctrine developed in the Tractatus and the subject of this article: the distinction between what can be shown and what can be said. To see how this is so, we need to look at some examples.

Sentences with sense express thoughts and correspond to the world. These are the ordinary sentences of language‒ sentences like “He cast the ring into the fire”. It is a sentence which has something plain in the world that corresponds to it; and, by virtue of this fact, it says something. But, in addition to saying something, this sentence, by virtue of its well-formed structure, also shows something. But what could this mean? Let’s look at the so-called “senseless” propositions to find out.

Other than sentences with sense, there are also sentences with no sense, i.e. that are senseless. These, according to Wittgenstein, are all the pure propositions of logic‒ propositions like p or ~p. These sentences say nothing but do show something by virtue of their form. For Wittgenstein, the “form” or structure of logic mirrors the structure of the world.

Lastly, there are the nonsensical propositions. These sentences fail by trying to express that which can only be shown. To this category belongs anything that matters in life, including but not limited to all metaphysical propositions, all statements about ethics, and any statements about the form of our logic or our language. So, for Wittgenstein, questions like “Does God love us?”, or “why is murder wrong?” ‒ or about pretty much anything in life which is of deep interest to the philosopher or the spiritualist or just the regular person ‒ are to be viewed as utter nonsense. That is, the questions or statements are nonsense, not the things or experiences in themselves.

What ought we to do upon realizing this? According to Wittgenstein, we ought to abandon our attempts at trying to talk about or explain these things– which includes abandoning philosophy itself, the sole purpose of which is to clarify the language problems that Wittgenstein has, in this book, now solved once and for all.

At the very end of the Tractatus, he writes:

6.54. My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb up beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)He must transcend these propositions, and then he will see the world aright.

He then ends his book with the following proposition:

7. What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.

~

After the publication of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein gave up his work at Cambridge and abandoned philosophy. He moved to Austria and became a school teacher– at least for a time. His philosophical mind would never rest, and he would eventually return to philosophy. And what a return it was.

To end, I want to leave you with a short poem. Not just any poem, but the very poem that Wittgenstein thought perfectly exemplified the distinction between what can be said and what can only be shown. See what you think.

“Count Eberhard’s Hawthorn”

Count Eberhard Rustle-Beard,

From Württemberg’s fair land,

On holy errand steer’d

To Palestina’s strand.

The while he slowly rode

Along a woodland way;

He cut from the hawthorn bush

A little fresh green spray.

Then in his iron helm

The little sprig he plac’d;

And bore it in the wars,

And over the ocean waste.

And when he reach’d his home;

He plac’d it in the earth;

Where little leaves and buds

The gentle Spring call’d forth.

He went each year to it,

The Count so brave and true;

And overjoy’d was he

To witness how it grew.

The Count was worn with age

The sprig became a tree;

‘Neath which the old man oft

Would sit in reverie.

The branching arch so high,

Whose whisper is so bland,

Reminds him of the past

And Palestina’s strand.

Why did Wittgenstein think this poem showed something which could not be said? As you can probably imagine, he didn’t say.

-AW